If you're familiar with low-budget horror flicks and/or video-game-to-movie adaptations, chances are you've heard of Uwe Boll. Even if you're not familiar with Boll's cinematic output, you've more than likely heard opinions on the guy's work, and, in all likelihood, those opinions have not exactly been complimentary. If Boll's work and name is a mystery to you, here's all you need to know: he's renowned for making terrible video game adaptations, his original work sucks too, he's had more films on the Internet Movie Database's Bottom 100 at one time than any other filmmaker (living or dead), he is widely regarded as the worst director in history, and he's able to make Ed Wood look competent. With 1968 Tunnel Rats, Boll continues to prove his uncanny ability as a versatile director: he's outrageously awful in every genre. Upfront: despite the fact I detest Uwe Boll, I wanted to like this particular movie. Truly, I did. The trailer was very promising. Alas, I must've forgotten I was dealing with Boll, because it's his trademark to turn movies with potential into absolute duds.

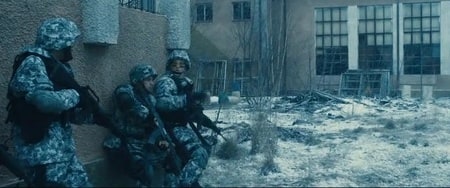

1968 Tunnel Rats (shortened to just Tunnel Rats in some corners) is set during the Vietnam War, but is not a typical jungle warfare movie. Boll's film focuses on an American army platoon that have copped the unenviable task of infiltrating the complex network of underground tunnels used by the Viet Cong to move around undetected and plan clever ambushes. Unfortunately for the soldiers, a dangerous task lies ahead of them: crawling along these narrow, unlit passageways peppered with booby traps and armed VC soldiers. If there's one thing Boll managed to skilfully achieve here, it's capturing the claustrophobic disposition of these tunnels, and the air of uncertainty around every narrow twist and turn. Alas, the impressive recreation of these tunnels is the only thing remotely successful about Tunnel Rats.

Almost immediately into the movie, the clichés begin to roll in fast and furious. The first 30 minutes or so is spent in exposition mode as the central characters are loosely established. Problem is, they're all stock characters: one solider misses his mother, another has a girl back home, their leader is a hardened career man, and someone wants to open a restaurant following their tour of duty. You get the idea. These archetypes are forgivable because these are the type of men you'd stumble upon in an American platoon, but what's unforgivable is the character development and the dialogue. Every character is two-dimensional, unremarkable, and interchangeable. No names ever stuck due to the lack of memorable faces, distinguishing features and killer dialogue. Worst of all, you never care about them. There's no reason to care about them. They're boring. Unsurprisingly, the script was improvised - the basic story was sketched out, but the actors were left to develop their own characters and write their own dialogue. It could not be more obvious, since the dialogue is also remarkably awkward and permeated with an unrealistic amount of swearing. Other Vietnam movies like Platoon and Apocalypse Now managed to offer interesting protagonists. Tunnel Rats makes us shrug and ask "Who cares?"

Other major detractors stem from Boll's trademarks: appalling direction and shoddy cinematography. For starters, there's a frequent lack of authority, with scenes playing out awkwardly. Editing is both lazy and choppy as well, with shots dragging on awkwardly long and some slapdash action set-pieces. In particular, a shot used during the opening sequence that observes a helicopter drags on for far too long and reeks of self-indulgence. At such a prolonged length, these shots don't engage; leaving a viewer bored and uncomfortable. Of course, Boll's use of shaky cam is abominable as well. It's mighty clear Boll has no idea how to effectively use this technique. Instead of tracking fight movements with the shaky cam (like, say, The Bourne Ultimatum), Boll shakes the camera for the sake of it, and the results don't achieve the desired effect. To the credit of Boll, his cinematic technique is gradually improving - Tunnel Rats does contain the director's most watchable action sequences to date. However, the fact one can only accept this as an exploitative action film rather than a war drama is disconcerting.

Predictably, Tunnel Rats is also marred by embarrassing technical inaccuracies. In the film, the U.S. soldiers use M16A2 and M655 Carbine Rifles, which were not developed until the 1980s and were certainly not used during the Vietnam War. The Americans are also shown wearing WW2-era uniforms and post-Vietnam web gear. The Viet Cong, meanwhile, are depicted using Norinco-Type 84S rifles instead of AK-47s, and they sport laughable hairstyles as if they just walked off the set of Tokyo Drift. To top it all off, the military outpost built deep into the jungle is without perimeter wires and guard towers. It's no wonder they were overrun so easily.

Tunnel Rats tries its hardest to deliver the message of "war is futile", but this is not explored past surface level. We see soldiers breaking down and crying, we see guns being fired, we see their terrifying ordeals in the tunnel, but we never feel their pain. This is due to the awful character development and the lack of nuance in every performance. More acclaimed movies based on the Vietnam War run a solid two or three hours, whereas Tunnel Rats boasts a scant 90-minute runtime. It feels like an action film first, and a potent war drama second. Look, this is Boll's best effort to date, but it's by no means a good or even a decent film. It's poorly acted, poorly directed, poorly handled, and the improvisation did not have the impact it should. The cover states "After Apocalypse Now, After Platoon Comes...Tunnel Rats". In this sense, Boll aimed extremely high but missed by an unbelievable margin (and this tagline is worded poorly...). There are plenty of superior movies set during the Vietnam War, and it's advisable you watch those and avoid this subpar effort.

3.9/10

Login

Login

Home

Home 183 Lists

183 Lists 1665 Reviews

1665 Reviews Collections

Collections

0 comments,

0 comments,