Rich in verve and cinematic personality, 1998's Velvet Goldmine perfectly encapsulates the glam rock scene of the 1970s and is one of the most distinct and fresh-feeling musicals of the '90s. Although not explicitly based on true events, the screenplay by writer-director Todd Haynes (I'm Not There) draws inspiration from real-life musicians, using personality traits and biographical details to create composite fictionalised characters reminiscent of David Bowie, Iggy Pop, and Lou Reed. With a recognisable cast of rising stars who were relatively unknown at the time, Velvet Goldmine is a terrific film that also takes visual inspiration from '70s music videos and the works of Nic Roeg and Robert Altman. The infectious sense of energy seldom wanes, with terrific music and unrelenting visual invention, though it might not be for all tastes.

1984 marks the tenth anniversary of an infamous publicity stunt wherein British glam rocker Brian Slade (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) staged his assassination on stage, faking his own death. To capitalise on public interest in Slade, British journalist Arthur Stuart is assigned to write an article on the elusive entertainer, who withdrew from public life after receiving severe backlash for his death hoax. Beginning the research process, Stuart tracks down several key figures in Slade's life and career, including his first manager, Cecil (Michael Feast) and his wife, Mandy (Toni Collette), who illuminate parts of the singer's professional and personal life. Early in Slade's career, he gained a new manager in Jerry Devine (Eddie Izzard) and showed support for gay culture in the mainstream press, making his bisexuality clear. When Slade first arrived in the United States, the Brit befriended and began working with American rock star Curt Wild (Ewan McGregor), but their tenuous relationship did not last. Stuart immerses himself deeper into the case, which holds significant personal meaning to him, as he idolised Slade as a teenager, and gained confidence through the bisexual singer to come out as gay.

With a structure deliberately reminiscent of Citizen Kane, Velvet Goldmine is non-linear and largely episodic, delving into the lives and backgrounds of its various eccentric characters. Haynes refuses to dwell on a single train of thought for too long, progressing through flashbacks, quirky musical interludes, sex scenes (including an amusing moment with a sex doll) and a range of bizarre non-sequiturs across a range of locations and settings, all delivered with the utmost energy. It consistently feels fresh and exciting, the cinematic equivalent of an exquisite, feverish rock dream. Although jumpy, the narrative nevertheless remains coherent for the most part, with Arthur and his investigation anchoring the story, providing momentum and purpose. The script's verbiage is uniquely engaging and poetic, with portions of dialogue reportedly derived from the writings of Oscar Wilde, whom the movie portrays as the progenitor of glam rock. Due to the film's fast-paced energy, the more conventional dramatic scenes in the third act do stand out and feel noticeably slower, but Haynes's sturdy direction combined with the engaging performances keep the proceedings interesting until the end.

Haynes deploys visual techniques galore throughout Velvet Goldmine, from transitions to stylised credits and different shutter speeds. The style is all the more impressive given that the film was produced the old-fashioned way before computers simplified the process for digital effects. The production design is magnificent, with the movie effortlessly recreating the '70s and '80s, especially nailing the distinct sense of fashion. Understandably, music plays a large part in Velvet Goldmine, and the selected songs seemingly influenced the editorial process, with scenes edited to match each track. Haynes hits the ground running with the delightful, infectiously energetic opening credits sequence set to Brian Eno's Needle in the Camel's Eye, which perfectly sets the tone. The soundtrack also features the likes of Iggy Pop, Roxy Music, Lou Reed, T. Rex, Placebo, and (regrettably) Gary Glitter, furthering the astonishing sense of time and place and giving the movie its unique atmosphere and flavour. Despite carrying the title of a David Bowie track, and despite Brian's deliberate resemblance to the late pop star, the film does not use Bowie's music, as he did not approve of the production despite the director hoping for his blessing.

Still relatively fresh from 1996's Trainspotting but still a year away from Star Wars, McGregor gives it his all here and disappears into the role of Curt Wild, who is a combination of Iggy Pop and Lou Reed. With long hair and outlandish fashion, McGregor embodies pop star traits with utmost abandon, even doing his own singing. Bale is more of a straight man (an ironic term for this character), a relatively normal man navigating the zany world of glam rock. Meanwhile, Jonathan Rhys Meyers convincingly looks the part of an eccentric glam rock singer with a dizzying array of ridiculous outfits and makeup styles. Other performers also make a positive impression here, particularly Australian actress Toni Collette, who creates a distinct and fascinating character with Mandy.

Admittedly, Velvet Goldmine comes up short in terms of emotion, and the style outweighs the substance. But with such a striking sense of style combined with razor-sharp editing and spirited performances from a superb cast, the movie confidently holds together. Its themes about gay acceptance are subtle but relevant, giving the movie some thematic significance beyond its surface-level pleasures. Especially for viewers who can appreciate a touch of surrealism, Velvet Goldmine is a gem.

7.8/10

Infectiously energetic and enjoyable

Posted : 1 year, 1 month ago on 17 April 2024 06:24

(A review of Velvet Goldmine)

Posted : 1 year, 1 month ago on 17 April 2024 06:24

(A review of Velvet Goldmine) 0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Haunting portrait of a fractured nation

Posted : 1 year, 1 month ago on 15 April 2024 04:30

(A review of Civil War)

Posted : 1 year, 1 month ago on 15 April 2024 04:30

(A review of Civil War)Alex Garland's fourth feature-film undertaking as writer and director, 2024's Civil War is his most ambitious project to date, taking inspiration from iconic war movies (particularly Apocalypse Now) to create a haunting portrait of a fractured nation. Instead of a sprawling war movie examining each side and their respective viewpoints, Civil War is about journalists caught in the thick of combat, trying to stay alive while documenting the brutal madness. With Garland tackling such controversial subject matter, especially in light of America's political unrest in recent years, it is fortunate that the script does not take a political stance or represent propaganda. Instead, it's a cautionary tale in the vein of The Day After or Threads, showing the devastating consequences of another Civil War. Once again, Garland competently explores provocative ideas with a movie that runs less than two hours, as Civil War only clocks in at 109 minutes.

At an indeterminate point in the future, America is in the throes of a Second Civil War, with a dictatorial third-term President (Nick Offerman) leading loyal federal forces against several secessionist movements. Word begins to spread that a strong secessionist group known as the "Western Forces" (comprising of Texas and California) plans to make their final push for the capital to overthrow the President, in turn ending the war. Seasoned photojournalist Lee Smith (Kirsten Dunst) and her colleague, Joel (Wagner Moura), intend to travel to Washington, D.C. to interview the President before his possible defeat. Joining the pair is aging journalist Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson) and an aspiring young photographer named Jessie (Cailee Spaeny), who idolises Lee and wants to make it as a frontline war photojournalist. Hitting the road, the group begins their perilous journey to the nation's capital, traversing hundreds of miles, with Jessie becoming exposed to violent conflicts that test her resolve.

Garland wisely avoids politics, eschewing any exploration behind the reasoning for America's Second Civil War to concentrate on the raw fight for survival and the realities of living in battle zones. Garland emphasises the picture's apolitical stance with the Western Forces, a movement uniting soldiers from Texas (a notoriously red state) and California (a notoriously blue state). Civil War is about war journalism, and we observe the conflicts through the eyes of Lee and her colleagues, who must remain objective while capturing the harsh realities that the public might not otherwise see. Civil War does not ask us to take sides; instead, the survival of the central four characters is our primary concern. Furthermore, Garland explores the futility of war, with some factions no longer sure who they are fighting or why. Garland explores the various possibilities of a war-town America, from neutral refugee camps to a small town where residents live in blissful ignorance, unwilling to participate in the conflict as they strive to continue life as normal. However, with the movie amounting to an episodic tour through war-torn America, Civil War does begin to lose momentum in the second act, with Garland's screenplay needing a stronger unifying narrative thread. The developing friendship between Lee and Jessie gives the movie some much-needed humanity, but the story is not necessarily about these two, and Garland can only sustain the string of fragmented conflicts for so long.

The smaller set pieces deliberately lack scope as the group travels through rural American towns, but the spectacular climax in Washington takes full advantage of the premise's potential as Garland stages a spectacular extended gun battle through the nation's capital. Although Garland has dabbled in gunplay before, Civil War is his first balls-to-the-wall action film, and the results are sensational. The violence is brutal, uncompromising and vicious, though Garland also shows tact when necessary, never dwelling on gore or making the picture feel unnecessarily exploitative. Garland even depicts several key moments using a series of still photographs through the lens of Lee or Jessie's cameras. The smaller conflicts during the first two acts burst with almost unbearable tension, especially a nerve-rattling encounter involving an unpredictable soldier (played by the always-reliable Jesse Plemons), and Garland thankfully does not lose his way during the climax. Carrying the largest budget in A24's history (approximately $50 million), the technical presentation is superb, from the slick cinematography by Rob Hardy (Garland's regular collaborator) to the sensational visual effects and the sinister original score.

Dunst is excellent here, looking tired and worn after years of experience and conflict. This is not a performance about glamour or looking pretty; instead, Dunst's Lee Smith is burnt out and emotionally detached, desensitised to the violence surrounding her, though Jessie brings out more of her humanity. Equally excellent is Moura (Elite Squad, Narcos), who is initially charismatic and confident but gradually loses his cool throughout the proceedings as things continue to occur outside of his control, taking him to breaking point. Spaeny continues her rise to prominence here, delivering a rock-solid performance as an aspiring photojournalist. Through body language and her demeanour, she convincingly transforms from a naive girl into a confident woman, with the movie's events taking their toll on her. Other recognisable performers also make their mark, from Nick Offerman as the President to an unhinged Jesse Plemons, while Stephen McKinley Henderson is a warm and authoritative presence as Sammy.

With its slick and immaculately polished visuals, it's a shame that Civil War's storytelling is so fragmented. Although it certainly comes alive during various compelling and harrowing moments, it does not feel like a full and complete story, which particularly impacts momentum during the picture's second act. Nevertheless, Garland gets more right than wrong, ensuring that Civil War is another memorable and worthwhile feather in the director's cinematic cap after the 2022 misfire of Men.

7.2/10

At an indeterminate point in the future, America is in the throes of a Second Civil War, with a dictatorial third-term President (Nick Offerman) leading loyal federal forces against several secessionist movements. Word begins to spread that a strong secessionist group known as the "Western Forces" (comprising of Texas and California) plans to make their final push for the capital to overthrow the President, in turn ending the war. Seasoned photojournalist Lee Smith (Kirsten Dunst) and her colleague, Joel (Wagner Moura), intend to travel to Washington, D.C. to interview the President before his possible defeat. Joining the pair is aging journalist Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson) and an aspiring young photographer named Jessie (Cailee Spaeny), who idolises Lee and wants to make it as a frontline war photojournalist. Hitting the road, the group begins their perilous journey to the nation's capital, traversing hundreds of miles, with Jessie becoming exposed to violent conflicts that test her resolve.

Garland wisely avoids politics, eschewing any exploration behind the reasoning for America's Second Civil War to concentrate on the raw fight for survival and the realities of living in battle zones. Garland emphasises the picture's apolitical stance with the Western Forces, a movement uniting soldiers from Texas (a notoriously red state) and California (a notoriously blue state). Civil War is about war journalism, and we observe the conflicts through the eyes of Lee and her colleagues, who must remain objective while capturing the harsh realities that the public might not otherwise see. Civil War does not ask us to take sides; instead, the survival of the central four characters is our primary concern. Furthermore, Garland explores the futility of war, with some factions no longer sure who they are fighting or why. Garland explores the various possibilities of a war-town America, from neutral refugee camps to a small town where residents live in blissful ignorance, unwilling to participate in the conflict as they strive to continue life as normal. However, with the movie amounting to an episodic tour through war-torn America, Civil War does begin to lose momentum in the second act, with Garland's screenplay needing a stronger unifying narrative thread. The developing friendship between Lee and Jessie gives the movie some much-needed humanity, but the story is not necessarily about these two, and Garland can only sustain the string of fragmented conflicts for so long.

The smaller set pieces deliberately lack scope as the group travels through rural American towns, but the spectacular climax in Washington takes full advantage of the premise's potential as Garland stages a spectacular extended gun battle through the nation's capital. Although Garland has dabbled in gunplay before, Civil War is his first balls-to-the-wall action film, and the results are sensational. The violence is brutal, uncompromising and vicious, though Garland also shows tact when necessary, never dwelling on gore or making the picture feel unnecessarily exploitative. Garland even depicts several key moments using a series of still photographs through the lens of Lee or Jessie's cameras. The smaller conflicts during the first two acts burst with almost unbearable tension, especially a nerve-rattling encounter involving an unpredictable soldier (played by the always-reliable Jesse Plemons), and Garland thankfully does not lose his way during the climax. Carrying the largest budget in A24's history (approximately $50 million), the technical presentation is superb, from the slick cinematography by Rob Hardy (Garland's regular collaborator) to the sensational visual effects and the sinister original score.

Dunst is excellent here, looking tired and worn after years of experience and conflict. This is not a performance about glamour or looking pretty; instead, Dunst's Lee Smith is burnt out and emotionally detached, desensitised to the violence surrounding her, though Jessie brings out more of her humanity. Equally excellent is Moura (Elite Squad, Narcos), who is initially charismatic and confident but gradually loses his cool throughout the proceedings as things continue to occur outside of his control, taking him to breaking point. Spaeny continues her rise to prominence here, delivering a rock-solid performance as an aspiring photojournalist. Through body language and her demeanour, she convincingly transforms from a naive girl into a confident woman, with the movie's events taking their toll on her. Other recognisable performers also make their mark, from Nick Offerman as the President to an unhinged Jesse Plemons, while Stephen McKinley Henderson is a warm and authoritative presence as Sammy.

With its slick and immaculately polished visuals, it's a shame that Civil War's storytelling is so fragmented. Although it certainly comes alive during various compelling and harrowing moments, it does not feel like a full and complete story, which particularly impacts momentum during the picture's second act. Nevertheless, Garland gets more right than wrong, ensuring that Civil War is another memorable and worthwhile feather in the director's cinematic cap after the 2022 misfire of Men.

7.2/10

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

A wasted opportunity

Posted : 1 year, 1 month ago on 14 April 2024 07:16

(A review of Argylle)

Posted : 1 year, 1 month ago on 14 April 2024 07:16

(A review of Argylle)A spy action movie from Matthew Vaughn (Kick-Ass, Kingsman) that stars Henry Cavill has no business being as thoroughly underwhelming as 2024's Argylle. Following in the shadow of 2021's equally underwhelming The King's Man, Argylle is another overlong, plodding endeavour from the once-brilliant British filmmaker, and the movie wastes Cavill's immense talents on a thankless role. Indeed, there is an unmistakable sense of false advertising at play here, as several notable performers - Cavill (who receives top billing), John Cena, Samuel L. Jackson, Richard E. Grant, and even Dua Lipa - receive glorified cameos. Scripted by Jason Fuchs (Ice Age: Continental Drift, 2015's Pan), Argylle should be a clever, witty spy thriller in the vein of Mission: Impossible, but Vaughn misses the mark by a significant margin. Quirky and exciting highlights are present, including a few early set pieces and the presence of an adorable feline, but the experience becomes laborious and headache-inducing.

Introverted spy novelist Elly Conway (Bryce Dallas Howard) becomes an international sensation with her series of Argylle spy novels and is nearly ready to deliver her fifth book. However, she suffers from writer's block while trying to tidy up the book's ending, and she turns to her mother, Ruth (Catherine O'Hara), for assistance. Embarking on a train journey to visit her parents, Elly meets an actual spy named Aidan (Sam Rockwell), who informs her that her novels seemingly predict the future and a villainous organisation, known as the Division, is coming for her. While protecting Elly from waves of armed assassins, Aidan hopes to end the author's writer's block and inspire her to write the next chapter, hoping she will reveal how to stop the Division.

Argylle shows promise in its first 70 minutes or so, with a strong sense of intrigue and thrilling action sequences that demonstrate Vaughn's trademark stylistic flourishes, accompanied by Lorne Balfe's flavoursome original score and a selection of enjoyable songs. (Vaugn even makes heavy use of the new Beatles track, Now and Then.) But a major twist signifies the film's downward spiral at the halfway mark, and the production never recovers or finds its footing. As the screenplay begins doling out endless twists, the movie's spark rapidly dissipates, leading to a tedious and needlessly convoluted second half lacking energy and stylistic vigour. Vaughn normally satirises each genre he tackles, and perhaps satire was the intention here (similar to the heist episode of Rick and Morty), but the lack of meaty belly laughs is a problem, and the haphazard structure ruins a natural, engaging narrative flow. Worse, Vaughn dedicates much of the second act to monotonous exposition to clarify the over-complicated plot.

Although the more down-to-earth action sequences are a highlight (such as an early train fight), Vaughn seems lost when orchestrating the bigger set pieces, which appear unfinished. Stylised visuals are a big part of Vaughn's cinematic voice, with heavy digital effects giving his movies a distinct, hyperreal aesthetic. But the CGI throughout Argylle does not look appropriately stylised - instead, the digital effects just look poor and fake. The extended climactic battle sequence is a key offender, with some of the worst green-screen compositing in a major motion picture this decade. Despite a lofty $200 million budget (Vaughn's largest budget to date), the movie looks too phoney, and it is unclear where the money went. (One supposes that the actors took home handsome bonuses due to the unconventional streaming model, cancelling out the need for continuing royalties.) Normally, a visceral punch elevates Vaughn's movies, with R-rated bloodletting facilitating memorable kills and devilish ultraviolence. But Argylle is a vanilla, PG-13 affair.

Despite featuring prominently in marketing materials, Cavill and Cena do not even play a part in the actual proceedings, as they only represent characters in Elly's book. It's a tragic waste of the spirited performers, especially as Cavill's idealised Argylle character is far more interesting than Howard as Elly. Rockwell does bring comedic energy to the proceedings, showing yet again that he is one of the industry's most reliable character actors, but the material fails to adequately serve him. Especially during the second half, Rockwell has little to do. Elsewhere in the cast, seasoned professionals like Bryan Cranston, Samuel L. Jackson and Catherine O'Hara bring appropriate gravitas and make a positive impression.

Overlong and overindulgent, Argylle is a wasted opportunity, representing a rare misfire for Vaughn. It's not awful, but the sense of fun and excitement wanes long before the humdrum climax arrives, and the movie is not nearly as clever as it thinks it is.

5.6/10

Introverted spy novelist Elly Conway (Bryce Dallas Howard) becomes an international sensation with her series of Argylle spy novels and is nearly ready to deliver her fifth book. However, she suffers from writer's block while trying to tidy up the book's ending, and she turns to her mother, Ruth (Catherine O'Hara), for assistance. Embarking on a train journey to visit her parents, Elly meets an actual spy named Aidan (Sam Rockwell), who informs her that her novels seemingly predict the future and a villainous organisation, known as the Division, is coming for her. While protecting Elly from waves of armed assassins, Aidan hopes to end the author's writer's block and inspire her to write the next chapter, hoping she will reveal how to stop the Division.

Argylle shows promise in its first 70 minutes or so, with a strong sense of intrigue and thrilling action sequences that demonstrate Vaughn's trademark stylistic flourishes, accompanied by Lorne Balfe's flavoursome original score and a selection of enjoyable songs. (Vaugn even makes heavy use of the new Beatles track, Now and Then.) But a major twist signifies the film's downward spiral at the halfway mark, and the production never recovers or finds its footing. As the screenplay begins doling out endless twists, the movie's spark rapidly dissipates, leading to a tedious and needlessly convoluted second half lacking energy and stylistic vigour. Vaughn normally satirises each genre he tackles, and perhaps satire was the intention here (similar to the heist episode of Rick and Morty), but the lack of meaty belly laughs is a problem, and the haphazard structure ruins a natural, engaging narrative flow. Worse, Vaughn dedicates much of the second act to monotonous exposition to clarify the over-complicated plot.

Although the more down-to-earth action sequences are a highlight (such as an early train fight), Vaughn seems lost when orchestrating the bigger set pieces, which appear unfinished. Stylised visuals are a big part of Vaughn's cinematic voice, with heavy digital effects giving his movies a distinct, hyperreal aesthetic. But the CGI throughout Argylle does not look appropriately stylised - instead, the digital effects just look poor and fake. The extended climactic battle sequence is a key offender, with some of the worst green-screen compositing in a major motion picture this decade. Despite a lofty $200 million budget (Vaughn's largest budget to date), the movie looks too phoney, and it is unclear where the money went. (One supposes that the actors took home handsome bonuses due to the unconventional streaming model, cancelling out the need for continuing royalties.) Normally, a visceral punch elevates Vaughn's movies, with R-rated bloodletting facilitating memorable kills and devilish ultraviolence. But Argylle is a vanilla, PG-13 affair.

Despite featuring prominently in marketing materials, Cavill and Cena do not even play a part in the actual proceedings, as they only represent characters in Elly's book. It's a tragic waste of the spirited performers, especially as Cavill's idealised Argylle character is far more interesting than Howard as Elly. Rockwell does bring comedic energy to the proceedings, showing yet again that he is one of the industry's most reliable character actors, but the material fails to adequately serve him. Especially during the second half, Rockwell has little to do. Elsewhere in the cast, seasoned professionals like Bryan Cranston, Samuel L. Jackson and Catherine O'Hara bring appropriate gravitas and make a positive impression.

Overlong and overindulgent, Argylle is a wasted opportunity, representing a rare misfire for Vaughn. It's not awful, but the sense of fun and excitement wanes long before the humdrum climax arrives, and the movie is not nearly as clever as it thinks it is.

5.6/10

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Provocative and horrifying prequel

Posted : 1 year, 1 month ago on 9 April 2024 02:38

(A review of The First Omen)

Posted : 1 year, 1 month ago on 9 April 2024 02:38

(A review of The First Omen)Even for the most optimistic film-goers, the notion of a prequel to 1976's The Omen seems unnecessary and laughable, a shameless cash-grab motivated by commerce instead of artistic integrity. After all, with three sequels, a remake and a short-lived television series, the Omen franchise is no stranger to superfluous milking. Against all odds, however, 2024's The First Omen successfully breathes new life into the property, with screenwriters Tim Smith, Keith Thomas, and Arkasha Stevenson (making her directorial debut) finding fertile narrative ground for this prequel. Instead of trashy and dull, The First Omen is artful and moody - it feels more like an A24 release than a mainstream horror picture. Although not on the same level as Richard Donner's chilling masterpiece, it is a worthwhile companion piece that surpasses the hit-and-miss sequels.

In 1971, American novitiate Margaret (Nell Tiger Free) arrives at Vizzardeli Orphanage in Rome to take her vows and begin her new life of religious dedication. With assistance from Cardinal Lawrence (Bill Nighy), her eccentric roommate Luz (Maria Caballero), and the Abbess, Sister Silvia (Sônia Braga), Margaret becomes orientated with her new setting. She also meets a young artist named Carlita (Nicole Sorace), who is isolated from the other children and suffers mistreatment by the nuns. Margaret is intrigued by the unusual Carlita and forms a bond with her, though Father Brennan (Ralph Ineson) soon arrives to warn the American about her newfound friend. Due to waning faith around the world, Father Brennan believes that Catholic radicals are conspiring to bring about the birth of the antichrist, in turn creating fear to drive people back to the church.

Set amid the true-to-life political unrest in Italy during the 1970s, the story of The First Omen benefits from an element of mystery and intrigue, though the revelations will only truly surprise newcomers to the franchise. The feature clocks in at a beefy 120 minutes, which is unusually long for the genre, but Stevenson mostly manages to sustain interest and engagement throughout the proceedings, especially during the vicious second half when the church's plans come into focus and the fight for survival begins. Unfortunately, the ending feels like a cop-out, betraying the otherwise pitch-black tone and seemingly setting up a potential sequel. Considering there are several sequels to The Omen that explore Damien's future, The First Omen should feel more like a self-contained one-and-done story. Thankfully, aside from the sequel tease, the story seamlessly transitions into the 1976 film and makes for an effective double feature with the much-revered classic.

With gorgeous cinematography courtesy of Aaron Morton (2013's Evil Dead), the artistry on display throughout The First Omen is genuinely impressive, with atmospheric use of shadows and intriguing framing, even making use of mirrors. The visual gravitas separates The First Omen from less skilful horror offerings (for example, the 2006 remake of The Omen), while the use of sound amplifies the creepiness and horror. There are several memorable moments here, including a haunting birth sequence and a horrifying suicide, earning the picture's R rating. The digital effects are not immaculate (computer-generated flames never look quite right), but the illusion is convincing enough, with the finale providing some potent horror imagery. Although there are a few jump scares, Stevenson mainly relies on suspenseful atmosphere and an omnipresent sense of dread, supported by the unnerving, deliberately intrusive original score by Mark Korven (The Lighthouse, The Black Phone) that is reminiscent of Jerry Goldsmith's superlative soundtrack from the original movie. Equally impressive are the performances, with young Nell Tiger Free making a fantastic impression as Margaret and nailing all the requirements for the taxing role. She effortlessly portrays fear and panic, and gamely participates in some icky body horror moments. Other seasoned actors, including Ralph Ineson, Charles Dance and Bill Nighy, contribute to the movie's feeling of legitimacy, ensuring it does not feel like another B-grade genre offering.

In addition to being a rock-solid prequel to a timeless, terrifying classic, The First Omen is a terrific horror movie in its own right, emerging as one of 2024's best, most notable genre offerings. Despite a slow first half and an underwhelming ending, The First Omen delivers where it counts, establishing Stevenson as a filmmaker with a bright future ahead of her. Provocative and unnerving, the film will undoubtedly delight horror buffs.

7.4/10

In 1971, American novitiate Margaret (Nell Tiger Free) arrives at Vizzardeli Orphanage in Rome to take her vows and begin her new life of religious dedication. With assistance from Cardinal Lawrence (Bill Nighy), her eccentric roommate Luz (Maria Caballero), and the Abbess, Sister Silvia (Sônia Braga), Margaret becomes orientated with her new setting. She also meets a young artist named Carlita (Nicole Sorace), who is isolated from the other children and suffers mistreatment by the nuns. Margaret is intrigued by the unusual Carlita and forms a bond with her, though Father Brennan (Ralph Ineson) soon arrives to warn the American about her newfound friend. Due to waning faith around the world, Father Brennan believes that Catholic radicals are conspiring to bring about the birth of the antichrist, in turn creating fear to drive people back to the church.

Set amid the true-to-life political unrest in Italy during the 1970s, the story of The First Omen benefits from an element of mystery and intrigue, though the revelations will only truly surprise newcomers to the franchise. The feature clocks in at a beefy 120 minutes, which is unusually long for the genre, but Stevenson mostly manages to sustain interest and engagement throughout the proceedings, especially during the vicious second half when the church's plans come into focus and the fight for survival begins. Unfortunately, the ending feels like a cop-out, betraying the otherwise pitch-black tone and seemingly setting up a potential sequel. Considering there are several sequels to The Omen that explore Damien's future, The First Omen should feel more like a self-contained one-and-done story. Thankfully, aside from the sequel tease, the story seamlessly transitions into the 1976 film and makes for an effective double feature with the much-revered classic.

With gorgeous cinematography courtesy of Aaron Morton (2013's Evil Dead), the artistry on display throughout The First Omen is genuinely impressive, with atmospheric use of shadows and intriguing framing, even making use of mirrors. The visual gravitas separates The First Omen from less skilful horror offerings (for example, the 2006 remake of The Omen), while the use of sound amplifies the creepiness and horror. There are several memorable moments here, including a haunting birth sequence and a horrifying suicide, earning the picture's R rating. The digital effects are not immaculate (computer-generated flames never look quite right), but the illusion is convincing enough, with the finale providing some potent horror imagery. Although there are a few jump scares, Stevenson mainly relies on suspenseful atmosphere and an omnipresent sense of dread, supported by the unnerving, deliberately intrusive original score by Mark Korven (The Lighthouse, The Black Phone) that is reminiscent of Jerry Goldsmith's superlative soundtrack from the original movie. Equally impressive are the performances, with young Nell Tiger Free making a fantastic impression as Margaret and nailing all the requirements for the taxing role. She effortlessly portrays fear and panic, and gamely participates in some icky body horror moments. Other seasoned actors, including Ralph Ineson, Charles Dance and Bill Nighy, contribute to the movie's feeling of legitimacy, ensuring it does not feel like another B-grade genre offering.

In addition to being a rock-solid prequel to a timeless, terrifying classic, The First Omen is a terrific horror movie in its own right, emerging as one of 2024's best, most notable genre offerings. Despite a slow first half and an underwhelming ending, The First Omen delivers where it counts, establishing Stevenson as a filmmaker with a bright future ahead of her. Provocative and unnerving, the film will undoubtedly delight horror buffs.

7.4/10

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

A visceral action-thriller let down by dull pacing

Posted : 1 year, 1 month ago on 6 April 2024 10:36

(A review of Monkey Man)

Posted : 1 year, 1 month ago on 6 April 2024 10:36

(A review of Monkey Man)The directorial debut for Oscar-nominated British actor Dev Patel, 2024's Monkey Man is a vicious vigilante action-thriller steeped in Indian culture and religion. Although initially intended for Netflix, Jordan Peele viewed the movie and pushed for a theatrical release, believing that the movie was too good for a streaming debut. Monkey Man follows a recognisable formula for revenge movies, but it's denser than expected, as it critiques India's current sociopolitical landscape and shows support for India's transgender population. Unfortunately, the resulting movie is not exactly light on its feet, with Patel unable to sustain interest or momentum throughout the beefy two-hour running time. The visceral action highlights of Monkey Man are remarkable, but pacing is not the movie's strong suit, as it only genuinely roars to life in its final third.

Kid (Dev Patel) earns a meagre living on the illegal underground fighting circuit, going up against more skilled fighters for cash while wearing a gorilla mask. Calling himself "Bobby," Kid gains employment as a kitchen hand for Queenie (Ashwini Kalsekar), who oversees a criminal empire and provides drugs and prostitutes for wealthy VIP clients. Negotiating a promotion, Kid gains access to the VIP zone, where he sets his sights on the corrupt police chief, Rana Singh (Sikandar Kher), who was responsible for destroying Kid's village and murdering his mother. After a botched assassination attempt that nearly kills him, Kid finds support in spiritual leader Alpha (Vipin Sharma) and her group, who are sympathetic to his cause due to the tumultuous political situation in India.

Patel, who co-wrote the screenplay with Paul Angunawela and John Collee, attempts to add substance to the narrative by touching on relevant issues in India, including political corruption and the oppression of transgender people. However, it amounts to window dressing, and thankfully, Patel does not traverse into unwelcome political grandstanding. Nevertheless, turning Kid into the hero of transgender people feels incredibly contrived and unearned, especially since Kid does not have a personal connection to them. More successful is Kid's spiritual connection with the Indian deity Hanuman, while the climax occurs against the backdrop of Diwali. This type of material is rare in mainstream cinema, and it adds an artful angle to an otherwise standard-order revenge movie. Monkey Man's first act gradually builds, relying on intrigue as Kid works on planning and executing his vendetta of vengeance against Rana. But after Kid's first armed conflict, the picture quickly loses its way, leading to an extremely dull second act that never finds its groove or builds any momentum. The movie's generic structure becomes all the more apparent during the painfully slow second act, when a defeated Kid rebuilds his strength, finds spiritual enlightenment and trains in combat before returning to face Rana again. At a basic level, it's the plot of Rocky III.

When Monkey Man is locked in action mode, it delivers in spades, with superb fight choreography and spirited bloodshed, captured with impressive visual panache. The finale, in particular, is a stunner, with Kid relentlessly and efficiently working his way through scores of combatants. After a drab second act, the climactic showdown is worth the wait. Monkey Man is not another vanilla PG-13 endeavour but instead a vicious R-rated revenge film that does not hold back on the graphic violence, but Patel also shows enough tact, never dwelling on the bloodshed or making it feel gratuitous. Patel's apparent influences are vast, from Korean cinema (think A Bittersweet Life) to The Raid and the John Wick movies. (One character even references John Wick while Kid is shopping for firearms.) Patel's directorial inexperience is never apparent during the impressive action sequences, and there's even a distinct arthouse touch to several moments throughout the movie, making this more intriguing and refreshing than a more standard-order B-movie. Patel has a distinct vision for Monkey Man, making it all the more disheartening that the writing and editing fail to serve him sufficiently.

Juggling directorial duties with acting, Patel is remarkable as Kid, with the performer ably conveying fear and pain through facial expressions while confidently delivering during the chaotic action beats. Although not an obvious choice for an action hero, Patel's fighting skills are genuinely impressive. The only other recognisable performer here is Sharlto Copley (District 9), who enthusiastically plays a scumbag responsible for organising fights and manipulating match outcomes.

With more editorial discipline, Monkey Man would have been one of 2024's standout action movies, particularly since Patel supplements the revenge story with an intriguing sense of culture. As it is, the movie works in fits and starts, but the experience is fatiguing due to its prolonged two-hour running time. Nevertheless, Patel shows incredible promise as a filmmaker, and Monkey Man remains more interesting than any number of generic Hollywood misfires.

6.5/10

Kid (Dev Patel) earns a meagre living on the illegal underground fighting circuit, going up against more skilled fighters for cash while wearing a gorilla mask. Calling himself "Bobby," Kid gains employment as a kitchen hand for Queenie (Ashwini Kalsekar), who oversees a criminal empire and provides drugs and prostitutes for wealthy VIP clients. Negotiating a promotion, Kid gains access to the VIP zone, where he sets his sights on the corrupt police chief, Rana Singh (Sikandar Kher), who was responsible for destroying Kid's village and murdering his mother. After a botched assassination attempt that nearly kills him, Kid finds support in spiritual leader Alpha (Vipin Sharma) and her group, who are sympathetic to his cause due to the tumultuous political situation in India.

Patel, who co-wrote the screenplay with Paul Angunawela and John Collee, attempts to add substance to the narrative by touching on relevant issues in India, including political corruption and the oppression of transgender people. However, it amounts to window dressing, and thankfully, Patel does not traverse into unwelcome political grandstanding. Nevertheless, turning Kid into the hero of transgender people feels incredibly contrived and unearned, especially since Kid does not have a personal connection to them. More successful is Kid's spiritual connection with the Indian deity Hanuman, while the climax occurs against the backdrop of Diwali. This type of material is rare in mainstream cinema, and it adds an artful angle to an otherwise standard-order revenge movie. Monkey Man's first act gradually builds, relying on intrigue as Kid works on planning and executing his vendetta of vengeance against Rana. But after Kid's first armed conflict, the picture quickly loses its way, leading to an extremely dull second act that never finds its groove or builds any momentum. The movie's generic structure becomes all the more apparent during the painfully slow second act, when a defeated Kid rebuilds his strength, finds spiritual enlightenment and trains in combat before returning to face Rana again. At a basic level, it's the plot of Rocky III.

When Monkey Man is locked in action mode, it delivers in spades, with superb fight choreography and spirited bloodshed, captured with impressive visual panache. The finale, in particular, is a stunner, with Kid relentlessly and efficiently working his way through scores of combatants. After a drab second act, the climactic showdown is worth the wait. Monkey Man is not another vanilla PG-13 endeavour but instead a vicious R-rated revenge film that does not hold back on the graphic violence, but Patel also shows enough tact, never dwelling on the bloodshed or making it feel gratuitous. Patel's apparent influences are vast, from Korean cinema (think A Bittersweet Life) to The Raid and the John Wick movies. (One character even references John Wick while Kid is shopping for firearms.) Patel's directorial inexperience is never apparent during the impressive action sequences, and there's even a distinct arthouse touch to several moments throughout the movie, making this more intriguing and refreshing than a more standard-order B-movie. Patel has a distinct vision for Monkey Man, making it all the more disheartening that the writing and editing fail to serve him sufficiently.

Juggling directorial duties with acting, Patel is remarkable as Kid, with the performer ably conveying fear and pain through facial expressions while confidently delivering during the chaotic action beats. Although not an obvious choice for an action hero, Patel's fighting skills are genuinely impressive. The only other recognisable performer here is Sharlto Copley (District 9), who enthusiastically plays a scumbag responsible for organising fights and manipulating match outcomes.

With more editorial discipline, Monkey Man would have been one of 2024's standout action movies, particularly since Patel supplements the revenge story with an intriguing sense of culture. As it is, the movie works in fits and starts, but the experience is fatiguing due to its prolonged two-hour running time. Nevertheless, Patel shows incredible promise as a filmmaker, and Monkey Man remains more interesting than any number of generic Hollywood misfires.

6.5/10

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Underrated, gripping old-school adventure yarn

Posted : 1 year, 1 month ago on 5 April 2024 01:59

(A review of Black Sea)

Posted : 1 year, 1 month ago on 5 April 2024 01:59

(A review of Black Sea)A gripping, masculine submarine movie in the old-school action-adventure mould, Black Sea is a ripping film reminiscent of memorable classics like Kelly's Heroes and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. If the picture had been produced back in the 1950s or 1960s, it might have starred Clint Eastwood or Gregory Peck. But with the movie coming out in 2014, award-winning director Kevin Macdonald (The Last King of Scotland, Touching the Void) delivers a familiar type of adventure yarn with laudable contemporary polish and a fantastic selection of memorable character actors. Plus, even though the story seems straightforward and familiar, Black Sea has a few unexpected twists and surprises up its sleeve. Especially with CGI-laden blockbusters and superhero movies filling theatres, it is refreshing to witness a flick like Black Sea, which remains criminally underrated and overlooked.

A salvage expert and veteran submarine skipper, Robinson (Jude Law) has devoted decades of his life to underwater salvage at the cost of his marriage, with his wife (Jodie Whittaker) divorcing him and taking custody of their son. Despite his dedication, Robinson is laid off from his job at Agora, leaving him financially destitute and unable to make his child support payments. In desperation, Robinson agrees to captain an independent, illegal expedition to locate a sunken Nazi U-boat from World War II that contains millions of dollars worth of gold. Although Agora wishes to salvage it, the wreck lies in disputed waters off the Georgian coast, making it difficult to mount an official expedition. With funding from a shady venture capitalist (Tobias Menzies), Robinson gathers a selection of Russian and British personnel to crew an ancient Russian submarine as they set off on the dangerous mission. However, the British and Russian factions do not trust each other, leading to heightened tensions that only intensify when Robinson declares that they will receive an equal share, meaning that fewer surviving men means a bigger cut.

There is a recognisable formula to submarine movies, as such productions often involve overcoming unexpected vessel damage and tense underwater hostilities between crew members. With a script by television writer Dennis Kelly (making his theatrical film debut), Black Sea adheres to these recognisable genre tropes, but the picture's success is in the execution. The issues encountered by the crew are not easy to predict, and the film shows no sentimentality towards the characters who could die at any time. With things seldom going to plan, there's an incredible underlying sense of tension that is sometimes hard to tolerate. There is also a sense of gravitas to the writing, with tense character interactions generating further uneasiness. Plus, with an adult rating in place, the characters can swear during tense situations, heightening the sense of realism and danger. Additionally, Kelly's script subtly touches upon class and economic struggles. Robinson and his colleagues find themselves in a desperate situation after making an honest living, with the uncaring capitalist system abandoning them despite their skills and dedication. Robinson is particularly bitter, realising his personal sacrifice and labour only led to the monetary gain of a big corporation, leaving him with nothing except a broken marriage. Retrieving the gold not only represents his key to financial freedom; it also symbolises a middle finger to the powerful people and structures that oppress the working class. Luckily, these thematic underpinnings do not overwhelm the story.

Despite a meagre budget (reportedly a mere £8 million), Macdonald's visual treatment of the material is spectacular, with convincing special effects and intricate set design working to generate the illusion of being underwater at sea with this crew. The digital effects are not immaculate, but they are good enough, ensuring that Black Sea feels like a slick theatrical movie instead of a B-grade direct-to-video production. The smooth cinematography by Christopher Ross is especially accomplished, with the careful lighting facilitating a realistic look with shadowy interiors while ensuring the events are always comprehensible. Macdonald ratchets up the tension throughout the picture, getting plenty of mileage from the cramped, sweaty submarine interiors and the hothead crew who do not trust each other and cannot get along. It's unbearably intense at times, particularly when Robinson chooses to take the vessel through a narrow underwater canyon despite slim chances of survival while those onboard wonder if they can force their captain to surface. Furthermore, although there is humour in the picture's early stages, Macdonald wisely keeps things tense and serious as the situation becomes more grave. The high stakes and omnipresent sense of danger make Black Sea a gripping watch.

Creating well-drawn, distinct characters in an ensemble movie is tricky, but it is crucial to maximise audience engagement. Luckily, Black Sea excels in its compelling characterisations thanks to strong writing and robust performances from an ideal cast. Law is the most recognisable name in the ensemble, and he trades in his regular soft-spoken charisma for something gruff, rugged and completely unglamorous. Although not an obvious choice to fill this type of role, Law hits every note with utmost confidence, convincingly portraying Robinson's descent into madness as he prioritises retrieving the gold over the safety of his men. Equally impressive is Australian actor Ben Mendelsohn (Animal Kingdom, The Place Beyond the Pines) as a mentally unstable veteran diver who has been in and out of prison. Meanwhile, Scoot McNairy (Argo, 12 Years a Slave) is a perfect pick for the snivelling representative for the expedition's investor, and Michael Smiley (The World's End) provides ample colour playing a crew member who served with Robinson in the Navy. Newcomer Bobby Schofield also warrants a mention as a teenager who joins the submarine, much to the chagrin of the Russians, who perceive his presence as a bad omen.

There is something comforting about motion pictures like Black Sea, which is not exactly a life-changing movie, but it is incredibly well-executed. Without any unwelcome pretence or political agenda, it's a compelling and often armrest-clenching adventure story that delivers thrills with utmost competence. Despite a few scripting contrivances, Black Sea is sturdy manly entertainment.

7.9/10

A salvage expert and veteran submarine skipper, Robinson (Jude Law) has devoted decades of his life to underwater salvage at the cost of his marriage, with his wife (Jodie Whittaker) divorcing him and taking custody of their son. Despite his dedication, Robinson is laid off from his job at Agora, leaving him financially destitute and unable to make his child support payments. In desperation, Robinson agrees to captain an independent, illegal expedition to locate a sunken Nazi U-boat from World War II that contains millions of dollars worth of gold. Although Agora wishes to salvage it, the wreck lies in disputed waters off the Georgian coast, making it difficult to mount an official expedition. With funding from a shady venture capitalist (Tobias Menzies), Robinson gathers a selection of Russian and British personnel to crew an ancient Russian submarine as they set off on the dangerous mission. However, the British and Russian factions do not trust each other, leading to heightened tensions that only intensify when Robinson declares that they will receive an equal share, meaning that fewer surviving men means a bigger cut.

There is a recognisable formula to submarine movies, as such productions often involve overcoming unexpected vessel damage and tense underwater hostilities between crew members. With a script by television writer Dennis Kelly (making his theatrical film debut), Black Sea adheres to these recognisable genre tropes, but the picture's success is in the execution. The issues encountered by the crew are not easy to predict, and the film shows no sentimentality towards the characters who could die at any time. With things seldom going to plan, there's an incredible underlying sense of tension that is sometimes hard to tolerate. There is also a sense of gravitas to the writing, with tense character interactions generating further uneasiness. Plus, with an adult rating in place, the characters can swear during tense situations, heightening the sense of realism and danger. Additionally, Kelly's script subtly touches upon class and economic struggles. Robinson and his colleagues find themselves in a desperate situation after making an honest living, with the uncaring capitalist system abandoning them despite their skills and dedication. Robinson is particularly bitter, realising his personal sacrifice and labour only led to the monetary gain of a big corporation, leaving him with nothing except a broken marriage. Retrieving the gold not only represents his key to financial freedom; it also symbolises a middle finger to the powerful people and structures that oppress the working class. Luckily, these thematic underpinnings do not overwhelm the story.

Despite a meagre budget (reportedly a mere £8 million), Macdonald's visual treatment of the material is spectacular, with convincing special effects and intricate set design working to generate the illusion of being underwater at sea with this crew. The digital effects are not immaculate, but they are good enough, ensuring that Black Sea feels like a slick theatrical movie instead of a B-grade direct-to-video production. The smooth cinematography by Christopher Ross is especially accomplished, with the careful lighting facilitating a realistic look with shadowy interiors while ensuring the events are always comprehensible. Macdonald ratchets up the tension throughout the picture, getting plenty of mileage from the cramped, sweaty submarine interiors and the hothead crew who do not trust each other and cannot get along. It's unbearably intense at times, particularly when Robinson chooses to take the vessel through a narrow underwater canyon despite slim chances of survival while those onboard wonder if they can force their captain to surface. Furthermore, although there is humour in the picture's early stages, Macdonald wisely keeps things tense and serious as the situation becomes more grave. The high stakes and omnipresent sense of danger make Black Sea a gripping watch.

Creating well-drawn, distinct characters in an ensemble movie is tricky, but it is crucial to maximise audience engagement. Luckily, Black Sea excels in its compelling characterisations thanks to strong writing and robust performances from an ideal cast. Law is the most recognisable name in the ensemble, and he trades in his regular soft-spoken charisma for something gruff, rugged and completely unglamorous. Although not an obvious choice to fill this type of role, Law hits every note with utmost confidence, convincingly portraying Robinson's descent into madness as he prioritises retrieving the gold over the safety of his men. Equally impressive is Australian actor Ben Mendelsohn (Animal Kingdom, The Place Beyond the Pines) as a mentally unstable veteran diver who has been in and out of prison. Meanwhile, Scoot McNairy (Argo, 12 Years a Slave) is a perfect pick for the snivelling representative for the expedition's investor, and Michael Smiley (The World's End) provides ample colour playing a crew member who served with Robinson in the Navy. Newcomer Bobby Schofield also warrants a mention as a teenager who joins the submarine, much to the chagrin of the Russians, who perceive his presence as a bad omen.

There is something comforting about motion pictures like Black Sea, which is not exactly a life-changing movie, but it is incredibly well-executed. Without any unwelcome pretence or political agenda, it's a compelling and often armrest-clenching adventure story that delivers thrills with utmost competence. Despite a few scripting contrivances, Black Sea is sturdy manly entertainment.

7.9/10

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Fun, entertaining and visually outstanding

Posted : 1 year, 2 months ago on 28 March 2024 04:55

(A review of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow)

Posted : 1 year, 2 months ago on 28 March 2024 04:55

(A review of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow)A pulpy, visually striking throwback to classic Hollywood adventure pictures, 2004's Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow is a fascinating forgotten gem that deserves reappraisal and rediscovery. Taking its cues from comic books, Indiana Jones, science fiction serials and many more, Sky Captain is an undeniable case of style over substance, but the style is so impressive and aesthetically pleasing that it hardly matters. Written and directed by first-time filmmaker Kerry Conran, the picture has an intriguing premise and appealing (though one-dimensional) characters. However, the visual stylings take priority here, resulting in an altogether unique big-screen experience that miraculously holds up two decades later but does not resonate as deeply as it should.

An intrepid reporter working in New York City, Polly Perkins (Gwyneth Paltrow) is investigating the disappearances of six renowned world scientists. While following up on clues and leads, mysterious giant robots attack Manhattan, and the authorities call upon idealistic mercenary Joe Sullivan (Jude Law), a.k.a. "Sky Captain," and his private air force, known as the Flying Legion, to fight back. With the robot attack seemingly connected to the disappearance of the scientists, Polly and Joe set out on a globe-trotting expedition in search of madman Dr. Totenkopf (Sir Laurence Olivier) to uncover his plans before it is too late. Also assisting the pair is Joe's ace mechanic friend Dex (Giovanni Ribisi), and one of Joe's former flames, a proficient Navy pilot named Commander Franky Cook (Angelina Jolie).

Conran's script evidently strives to emulate classic Hollywood screwball comedies from the '30s and '40s with the sarcastic, snarky interplay between Polly and Joe (think His Girl Friday), but the dialogue unfortunately lacks the witty spark of a Billy Wilder screenplay. This is part of the film's overall lack of humanity and substance, with the feature primarily a visual experience instead of an emotional one. Without any emotional core and with a muddled narrative in need of more storytelling momentum, Sky Captain occasionally meanders, particularly during the midsection. The movie bizarrely alternates between the sublime and the mundane, with dramatic scenes often falling flat while the set pieces come alive with vigour and exhilaration.

Storytelling problems aside, the aesthetic presentation of Sky Captain is astounding, particularly for a production from 2004. There are shades of 1990s comic-book movies like The Rocketeer and The Shadow with its retrofuturistic production design and sense of lighthearted fun, while the robots themselves evoke memories of Brad Bird's The Iron Giant. Other influences are apparent, from German Expressionism to 1933's King Kong, and many more. Nevertheless, Sky Captain takes on a distinctive visual identity of its own and remains incredibly unique two decades later. The result of meticulous planning, intensive storyboards, 3D animatics, and even shooting the entire picture with stand-ins before principal photography, it is easy to be amazed by the breathtaking cinematic artistry on display. Admittedly, the blue-screen work is less than perfect, with some shots looking worse than others, and the digital effects are not photorealistic. However, the imperfections contribute to the movie's immense charm and are part of the intended aesthetic style, with the visuals looking stylised and hyper-realistic. Indeed, Conran did not intend for the feature to resemble reality. The array of locations, from New York City to Nepal and Tibet, ensure sufficient variety to maintain visual interest, with Conran consistently taking us to new and exciting places. One particularly rousing battle even takes place underwater with amphibious crafts and robots. Conran's handling of the action sequences is superb, while Sabrina Plisco's astute editing keeps the set pieces taut and stimulating. Thankfully, it is always easy to follow what is happening.

The cinematography by Eric Adkins takes its cues from classic movies (including Hollywood and German Expressionistic cinema), imbuing the picture with a distinctive sepia-toned colour palette, theatrical lighting, gorgeous framing and soft focus. One of the earliest features to be shot digitally, Sky Captain also exhibits a fine layer of film grain, making it even more unique in the realm of movies with a heavy reliance on digital effects. (Movies like Attack of the Clones, Revenge of the Sith and Sin City did not bother with film grain overlays.) Composer Edward Shearmur is likewise in sync with the material and its array of influences, creating a heroic, stirring and flavoursome original score reminiscent of classic adventure pictures. There are further audio homages, too, with the robot heat rays using the same sound effects as the Martian machines from 1953's The War of the Worlds. Meanwhile, the actors understand the assignment, with broad, scenery-chewing villainy and charismatic heroes, while Paltrow does exceptionally well as the peppy, determined reporter. Jolie, who could only work on the picture for three days, is fantastic as the sharp-tongued Navy commander, making the most of her limited screen time. Sir Laurence Olivier, who died in 1989, also appears from beyond the grave with a digital performance as Dr. Totenkopf. The filmmakers manipulated footage of a young Olivier to achieve this, and the effect is surprisingly convincing.

The singularity of Conran's vision is vital to the success of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, with the film's producer, Jon Avnet, openly acknowledging that this vision would not have survived the studio process. Despite its scripting and storytelling imperfections, Conran's immense talents as a visual craftsman are enormously apparent, with the picture not displaying any evidence of his directorial inexperience. The movie's abject failure at the box office remains an enormous injustice, especially since it was produced outside of the Hollywood system and was a labour of love for Conran, who pursued the project out of passion instead of commerce. With Hollywood blockbusters becoming more soulless and generic over time, watching a movie like Sky Captain is pleasantly enjoyable, as it's a fun and entertaining reminder of a bygone filmmaking era.

7.1/10

An intrepid reporter working in New York City, Polly Perkins (Gwyneth Paltrow) is investigating the disappearances of six renowned world scientists. While following up on clues and leads, mysterious giant robots attack Manhattan, and the authorities call upon idealistic mercenary Joe Sullivan (Jude Law), a.k.a. "Sky Captain," and his private air force, known as the Flying Legion, to fight back. With the robot attack seemingly connected to the disappearance of the scientists, Polly and Joe set out on a globe-trotting expedition in search of madman Dr. Totenkopf (Sir Laurence Olivier) to uncover his plans before it is too late. Also assisting the pair is Joe's ace mechanic friend Dex (Giovanni Ribisi), and one of Joe's former flames, a proficient Navy pilot named Commander Franky Cook (Angelina Jolie).

Conran's script evidently strives to emulate classic Hollywood screwball comedies from the '30s and '40s with the sarcastic, snarky interplay between Polly and Joe (think His Girl Friday), but the dialogue unfortunately lacks the witty spark of a Billy Wilder screenplay. This is part of the film's overall lack of humanity and substance, with the feature primarily a visual experience instead of an emotional one. Without any emotional core and with a muddled narrative in need of more storytelling momentum, Sky Captain occasionally meanders, particularly during the midsection. The movie bizarrely alternates between the sublime and the mundane, with dramatic scenes often falling flat while the set pieces come alive with vigour and exhilaration.

Storytelling problems aside, the aesthetic presentation of Sky Captain is astounding, particularly for a production from 2004. There are shades of 1990s comic-book movies like The Rocketeer and The Shadow with its retrofuturistic production design and sense of lighthearted fun, while the robots themselves evoke memories of Brad Bird's The Iron Giant. Other influences are apparent, from German Expressionism to 1933's King Kong, and many more. Nevertheless, Sky Captain takes on a distinctive visual identity of its own and remains incredibly unique two decades later. The result of meticulous planning, intensive storyboards, 3D animatics, and even shooting the entire picture with stand-ins before principal photography, it is easy to be amazed by the breathtaking cinematic artistry on display. Admittedly, the blue-screen work is less than perfect, with some shots looking worse than others, and the digital effects are not photorealistic. However, the imperfections contribute to the movie's immense charm and are part of the intended aesthetic style, with the visuals looking stylised and hyper-realistic. Indeed, Conran did not intend for the feature to resemble reality. The array of locations, from New York City to Nepal and Tibet, ensure sufficient variety to maintain visual interest, with Conran consistently taking us to new and exciting places. One particularly rousing battle even takes place underwater with amphibious crafts and robots. Conran's handling of the action sequences is superb, while Sabrina Plisco's astute editing keeps the set pieces taut and stimulating. Thankfully, it is always easy to follow what is happening.

The cinematography by Eric Adkins takes its cues from classic movies (including Hollywood and German Expressionistic cinema), imbuing the picture with a distinctive sepia-toned colour palette, theatrical lighting, gorgeous framing and soft focus. One of the earliest features to be shot digitally, Sky Captain also exhibits a fine layer of film grain, making it even more unique in the realm of movies with a heavy reliance on digital effects. (Movies like Attack of the Clones, Revenge of the Sith and Sin City did not bother with film grain overlays.) Composer Edward Shearmur is likewise in sync with the material and its array of influences, creating a heroic, stirring and flavoursome original score reminiscent of classic adventure pictures. There are further audio homages, too, with the robot heat rays using the same sound effects as the Martian machines from 1953's The War of the Worlds. Meanwhile, the actors understand the assignment, with broad, scenery-chewing villainy and charismatic heroes, while Paltrow does exceptionally well as the peppy, determined reporter. Jolie, who could only work on the picture for three days, is fantastic as the sharp-tongued Navy commander, making the most of her limited screen time. Sir Laurence Olivier, who died in 1989, also appears from beyond the grave with a digital performance as Dr. Totenkopf. The filmmakers manipulated footage of a young Olivier to achieve this, and the effect is surprisingly convincing.

The singularity of Conran's vision is vital to the success of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, with the film's producer, Jon Avnet, openly acknowledging that this vision would not have survived the studio process. Despite its scripting and storytelling imperfections, Conran's immense talents as a visual craftsman are enormously apparent, with the picture not displaying any evidence of his directorial inexperience. The movie's abject failure at the box office remains an enormous injustice, especially since it was produced outside of the Hollywood system and was a labour of love for Conran, who pursued the project out of passion instead of commerce. With Hollywood blockbusters becoming more soulless and generic over time, watching a movie like Sky Captain is pleasantly enjoyable, as it's a fun and entertaining reminder of a bygone filmmaking era.

7.1/10

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

An overlooked character-based dark comedy

Posted : 1 year, 2 months ago on 24 March 2024 08:58

(A review of Ghost World)

Posted : 1 year, 2 months ago on 24 March 2024 08:58

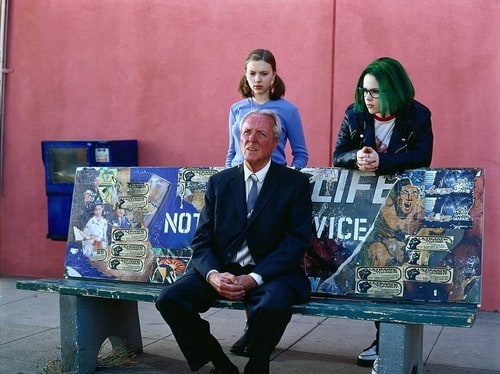

(A review of Ghost World)Adapted from the 1990s graphic novel series by Daniel Clowes, 2001's Ghost World is a wonderful, deadpan, darkly comedic depiction of post-high school teenage angst with its inherent ups and downs. Clowes was involved in adapting his comic for the big screen, collaborating with director Terry Zwigoff (Crumb, Bad Santa) on the screenplay that received an Academy Award nomination. Eschewing traditional Hollywood teen comedy conventions, Ghost World is a refreshing and unusual film in its conception and execution; it's challenging to predict each story development, and the film concludes on a deliberately ambiguous, open-ended note that leaves room for interpretation.

After graduating from high school, best friends and misanthropic social outcasts Enid (Thora Birch) and Rebecca (Scarlett Johansson) have no plans for their future beyond finding jobs and living together. Refusing to follow the crowd, college is not on the cards for Enid or Rebecca, who struggle to define themselves and despise everything popular. While Rebecca gets a job working at a coffee house, Enid finds it challenging to let go of the comfort of adolescence, floating aimlessly through life as she spends most of her time at a remedial art class that she must pass to obtain her high school diploma. Enid cannot hold a job for long and begins a semi-romantic relationship with a timid jazz fan named Seymour (Steve Buscemi), who is much older than her and cannot connect with other people. Enid is fascinated and intrigued by the lonely Seymour, and she tries to help him find love to fill the void in his life. However, Enid and Rebecca's different priorities and diverging lives begin to take a toll on their friendship, while Seymour finding a girlfriend threatens to drive him away from Enid.

Ghost World is not a heavily plot-driven movie, and Zwigoff maintains an unhurried pace as he observes Enid refusing to find a purpose in life and listlessly meandering while Rebecca successfully adapts to adult life. The narrative's distinct rhythm, which does not exactly conform to a regular three-act structure, reflects the vagueness of adult life after high school, with Enid defiantly remaining in her rut while things change and progress around her. In many ways, the film is about the challenges of teenagers finding their own post-adolescent identity; Enid and Rebecca define themselves by mocking people who conform to society's expectations but are in danger of becoming the same type of people they are ridiculing. With a focus on themes and mood instead of plot, Ghost World is mainly about the oddball characters and their witty interactions, and the picture soars in this respect. As expected from the director behind 2003's Bad Santa, laughs are frequent throughout Ghost World, from uproarious non-sequiturs (including a heated confrontation between a store owner and a shirtless patron) to cutting, sarcastic one-liners. The dialogue is also insightful, exploring loneliness and geekiness, and the film gleefully satirises the pretentiousness associated with the art world.

The characters inhabiting Ghost World are not easy to categorise and do not conform to recognisable character types. Additionally, the characters miraculously feel like three-dimensional people instead of caricatures, with the screenplay allowing ample breathing room for dramatic scenes and character development. Credit also goes to the actors, who brilliantly bring these people to life. Birch and Johansson are an ideal leading pair, with both young actresses nailing their characters' cynical and misanthropic dispositions while coming across as authentic instead of caricaturish. With Birch emerging as the film's protagonist, she has the most to work with, and she portrays Enid's various characteristics and quirks without missing a beat. In addition to her pronounced quirkiness and bitter sarcasm, there is an underlying sense of melancholy, with the film's events taking an emotional toll on Enid. Meanwhile, Buscemi makes for a pitch-perfect Seymour. Buscemi is a superb character actor, and this might be his finest performance to date. Modelling his character's appearance and interests after director Zwigoff, Buscemi wholly immerses himself into the role with distinct mannerisms, line deliveries and body language. Withdrawn, awkward, and painfully shy, it's a transformative performance and the furthest thing from a traditional romantic lead. According to Zwigoff, Buscemi found playing the character of Seymour so uncomfortable that he immediately changed his clothes after filming wrapped each day.

From a technical perspective, Ghost World is comparatively basic, with unspectacular cinematography and little in the way of visual flourishes. Indeed, Zwigoff mostly lets the actors and the sharp dialogue speak for themselves, and the picture's somewhat drab appearance, which is deliberately reminiscent of the comic book, may not appeal to film-goers accustomed to slick, vibrant digital photography. Your mileage may vary. However, the picture excels in the brilliantly intuitive editing and the soundtrack, with oddball old jazz records almost omnipresent whenever characters spend time in Seymour's home. There is melancholic original music courtesy of composer David Kitay, but the soundtrack is primarily diegetic, comprising of vintage, atmospheric blues tracks.

With its laid-back pacing and unconventional characters, Ghost World is not for all tastes, and it makes for a refreshing change from other, more formulaic teen movies. Not everything works, and it is easier to appreciate than outright love, but this overlooked gem nevertheless deserves your attention, especially if you enjoy thoughtful character-based movies with sharp and insightful dialogue.

7.9/10

After graduating from high school, best friends and misanthropic social outcasts Enid (Thora Birch) and Rebecca (Scarlett Johansson) have no plans for their future beyond finding jobs and living together. Refusing to follow the crowd, college is not on the cards for Enid or Rebecca, who struggle to define themselves and despise everything popular. While Rebecca gets a job working at a coffee house, Enid finds it challenging to let go of the comfort of adolescence, floating aimlessly through life as she spends most of her time at a remedial art class that she must pass to obtain her high school diploma. Enid cannot hold a job for long and begins a semi-romantic relationship with a timid jazz fan named Seymour (Steve Buscemi), who is much older than her and cannot connect with other people. Enid is fascinated and intrigued by the lonely Seymour, and she tries to help him find love to fill the void in his life. However, Enid and Rebecca's different priorities and diverging lives begin to take a toll on their friendship, while Seymour finding a girlfriend threatens to drive him away from Enid.

Ghost World is not a heavily plot-driven movie, and Zwigoff maintains an unhurried pace as he observes Enid refusing to find a purpose in life and listlessly meandering while Rebecca successfully adapts to adult life. The narrative's distinct rhythm, which does not exactly conform to a regular three-act structure, reflects the vagueness of adult life after high school, with Enid defiantly remaining in her rut while things change and progress around her. In many ways, the film is about the challenges of teenagers finding their own post-adolescent identity; Enid and Rebecca define themselves by mocking people who conform to society's expectations but are in danger of becoming the same type of people they are ridiculing. With a focus on themes and mood instead of plot, Ghost World is mainly about the oddball characters and their witty interactions, and the picture soars in this respect. As expected from the director behind 2003's Bad Santa, laughs are frequent throughout Ghost World, from uproarious non-sequiturs (including a heated confrontation between a store owner and a shirtless patron) to cutting, sarcastic one-liners. The dialogue is also insightful, exploring loneliness and geekiness, and the film gleefully satirises the pretentiousness associated with the art world.