Since its publication in 1843, Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol has been adapted across various mediums (including stage, opera, radio, television and film) to varying degrees of success and quality. One of the best versions to date is this 1971 animated television special, and unfortunately, it is also one of the most forgotten and underrated retellings of Dickens's classic novella. Helmed by Richard Williams (The Thief and the Cobbler) and produced by animation legend Chuck Jones (Looney Tunes, 1966's How the Grinch Stole Christmas!), 1971's A Christmas Carol was initially created as a television special but received a theatrical release due to the high animation quality, and it subsequently earned an Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film. As of 2024, it is the only cinematic rendering of Dickens's supernatural Christmas tale to win an Oscar, and it is highly deserving of this prestigious honour.

A Christmas Carol's story is well-known; therefore, a brief plot synopsis will suffice. Set in 19th-century London, the story concerns a bitter old miser more concerned with his own affluence than human compassion, Ebenezer Scrooge (Alastair Sim). On Christmas Eve, he receives a visit from his deceased former business partner, Jacob Marley (Michael Hordern), who warns Scrooge about the error of his ways and the need to atone for his wrongdoings. Although Scrooge tries to dismiss Marley's ghostly visit as a figment of his imagination, three more spirits visit him during the night: the Ghost of Christmas Past (Diana Quick), the Ghost of Christmas Present (Felix Felton), and the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, all of whom offer grim visions and a chance at redemption.

Unlike the numerous feature-length retellings, this A Christmas Carol clocks in at a scant 25 minutes. Fortunately, its brevity is incredibly beneficial, as director Williams does not waste a single frame. The adaptation hews closely to Dickens' original vision (in fact, the film does not credit a screenwriter - only Dickens), briskly moving through the well-worn plot without ever growing dreary or monotonous. Furthermore, this concise short still packs a huge emotional punch and efficiently delivers all the thought-provoking messages audiences associate with this timeless morality tale. Admittedly, a few moments feel slightly rushed (perhaps an extra five minutes could have catapulted the film to perfection), but this was probably the best adaptation possible within a 25-minute timeframe.

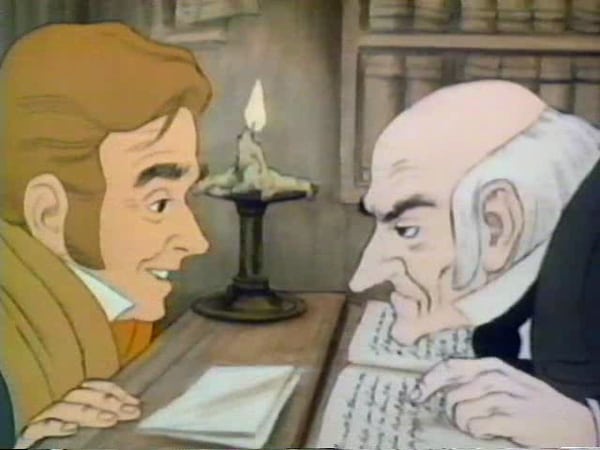

For the engaging visual style, the animation team drew inspiration from the original 19th-century illustrations by John Leech and later drawings by Milo Winter for 1930s editions of the book. A Christmas Carol may look dated compared to contemporary animated features, but it remains impressive nevertheless, with innovative pans, zooms and scene transitions giving the director's vision a distinctive look. The skilled artists also use lighting to superb effect, capturing the elegiac austerity of London in the mid-1800s. Williams wanted his retelling of A Christmas Carol to be dark and gloomy, doing justice to the story's bleak supernatural elements. Consequently, Williams plays up the horror aspects, and this version is genuinely scary at times with its unsettling ghost designs and use of darkness. As a result, a title card prefaces the film to warn viewers that this is "A Ghost Story of Christmas." Reportedly, the film fell into obscurity because television stations deemed it "too scary for children," making them reluctant to purchase the broadcast rights.

Narrated with gripping passion by legendary British actor Sir Michael Redgrave, 1971's A Christmas Carol is notable for bringing back Alastair Sim and Michael Hordern, who starred in the acclaimed 1951 iteration of A Christmas Carol (a.k.a. Scrooge). As a result of his highly acclaimed performance as Scrooge in the 1951 picture, critics and viewers frequently regard the late Sim as the best big-screen Scrooge. Fortunately, Sim's work here is equally excellent, reprising the role with relish. With twenty years separating his two performances, Sim sounds older and more gravelly, giving the role more gravitas. The supporting actors also turn in wonderful performances, with Hordern giving Jacob Marley an unsettling edge to complement the spooky, ghostly visuals, while Diana Quick and Felix Felton are hugely engaging as their respective ghosts.

Over fifty years since its release, this incarnation of Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol remains one of the best and most visually distinctive to date. It is fast-paced and visually stunning, and it does a remarkable job of conveying the grim nature of Scrooge's journey and the uplifting disposition of his redemptive epiphany. Unfortunately, not many viewers are aware of this iteration despite its Academy Award win, making it ripe for rediscovery.

8.2/10

Login

Login

Home

Home 183 Lists

183 Lists 1662 Reviews

1662 Reviews Collections

Collections

0 comments,

0 comments,