1983's Superman III is the first entry in this series without any input from Superman director Richard Donner or screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz, whose conceptual ideas elevated the flawed but still serviceable Superman II, which was heavily rewritten and reshot after producers Alexander and Ilya Salkind fired Donner. Thus, the Salkinds handed the keys for Superman III over to Superman II's substitute director, Richard Lester, and the screenwriting pair of David and Leslie Newman. Although the Newmans retain a credit on the original Superman, Donner detested their comedic scripts for the first two pictures to such an extent that he hired Mankiewicz to rewrite them. Donner and Mankiewicz had plans for further Superman films and intended to use Brainiac as a villain, but Lester and the Newmans foolishly disregard the years of comic book villains and stories for their Superman III, instead creating a low-grade Richard Pryor comedy vehicle that lacks the lustre, sincerity, scope and gravitas of 1978's Superman. The law of diminishing returns is in full effect here.

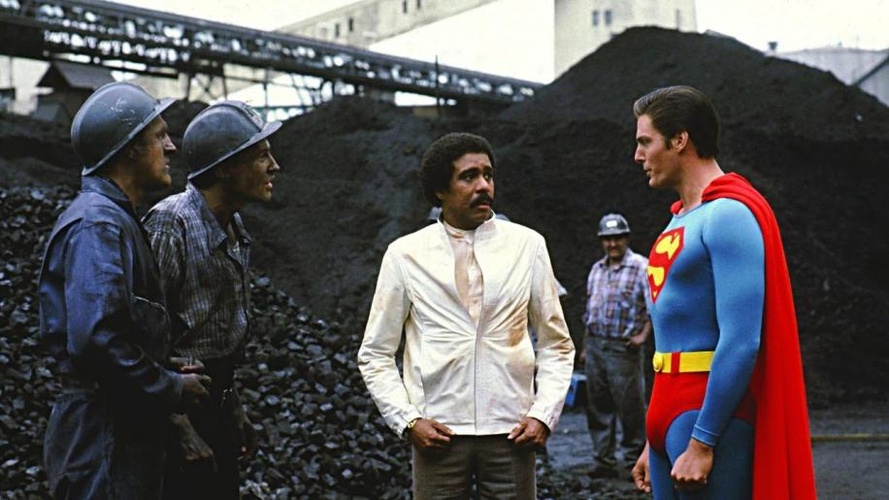

After Metropolis's unemployment agency stops his benefits, Gus Gorman (Richard Pryor) sets his sights on becoming a computer programmer and gets a job at Webscoe Industries. Shocked by his low salary, Gus concocts a scheme to embezzle thousands of dollars from the company, which brings him to the attention of Webscoe's CEO, Ross Webster (Robert Vaughn). Although Gus broke the law, Webster sees him as an asset and blackmails the computer programmer into helping him with a scheme to dominate the world financially. Meanwhile, Clark Kent/Superman (Christopher Reeve) returns to Smallville for his high school reunion, where he reconnects with his childhood friend, Lana Lang (Annette O'Toole). Lana is now a divorcee who's raising a son, Ricky (Paul Kaethler), and they soon start spending time together. When Superman interferes with Webster's plans, the millionaire orders Gus to find a way to eliminate the Kryptonian hero. Although Gus's attempt to make synthetic Kryptonite fails to kill Superman, it corrupts him and turns him into a selfish menace, gravely affecting his public image.

Superman III does not feel like an organic continuation of Superman because Lester turns the threequel into a farce. The director fills the threequel with comedic tomfoolery, from slapstick nonsense (the green and red men in the traffic lights fighting each other) to Pryor's overacting and improvising. The comical tone is a radical departure from the original Superman, for which Donner and Mankiewicz believed earnestness was crucial. Superman III is powerfully stupid at times, with Gus managing to bypass all computer security by typing simple requests. The writers also seem to believe that even basic model computers in the 1980s could do virtually anything, including reprogramming satellites to control the weather. Additionally, even if viewers can accept Superman III as a non-serious comedy, it is not overly funny. The script lacks wit and belly laughs, while Lester seemingly relies on Richard Pryor to try to create the comedy by mugging the camera. Pryor, who was only cast after he told Johnny Carson that he would like to feature in a Superman movie, is a gifted comedian with several notable comedies to his name (Stir Crazy, See No Evil, Hear No Evil), but he cannot bring the flick to life despite his best efforts.

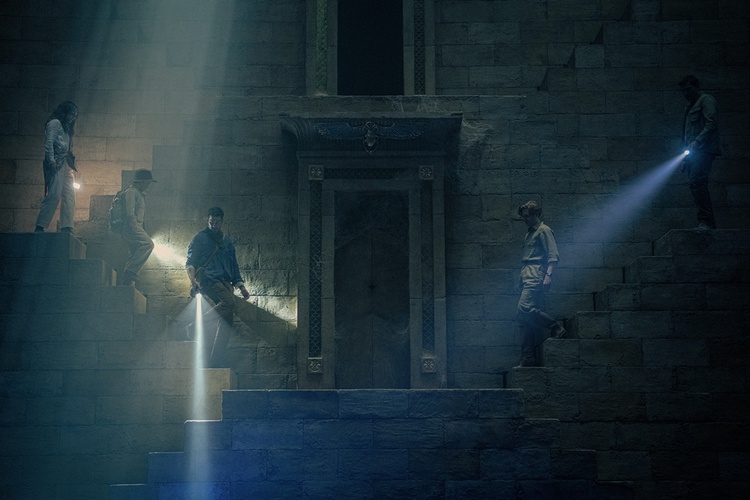

The concept of an evil Superman is easily the most promising aspect of Superman III, but the film does not fully capitalise on it. Indeed, we only get to see evil Superman 'fixing' the leaning Tower of Pisa, complete with awful compositing, in front of a street vendor who sells souvenir towers, and he also blows out the Olympic Flame. Lester plays both scenes for laughs. More sinister is a scene in which Superman causes an oil spill, but that is about as interesting as it gets. A dark Superman would do more than commit acts of petty vandalism, and it would be more effective to see him tearing people apart or stealing gold from secure vaults. Admittedly, however, Reeve is genuinely frightening when Superman lashes out in anger during a drunken outburst, and the fight between Clark Kent and the corrupted Superman in the junkyard is easily the best set piece in the picture. One cannot help but wonder what Superman III would be like if the story were more focused on Superman turning evil. Unfortunately, with the film resolving the corrupted Superman arc after a mere 20 minutes, it amounts to a minor distraction.

The special effects throughout Superman III range from serviceable to laughably goofy. Most of the flying scenes look convincing, with excellent wirework and respectable green-screening for the era, but a sequence involving Superman freezing a lake and picking up the enormous icicle looks howlingly awful, even for the 1980s. Another mistake was bringing back Superman II composer Ken Thorne, as the resulting soundtrack lacks the magnificence, nuance and gravitas of John Williams's triumphant compositions on the original Superman. Thorne's rendition of Williams's iconic Superman theme sounds like a lifeless imitation, and the rest of the score resembles something from a generic comedy rather than a superhero film. On a more positive note, The Beatles' cover version of "Roll Over Beethoven" plays during Clark's high school reunion, a fitting track that also serves as a tribute to Lester's directorial work on A Hard Day's Night and Help! with the British rock band. Thankfully, too, Lester's direction is more dynamic here, with the film feeling less slapdash than the hastily-reshot Superman II, but the quality of Superman III does vary from scene to scene.

Christopher Reeve remains note-perfect as Clark Kent and Superman, with the two identities remaining wholly distinct thanks to his nuanced performance. The dull material, thankfully, does not diminish Reeve's boyish charm, and the sequence of Clark fighting evil Superman is among Reeve's finest work in the series. Additionally, Reeve and the lovely Annette O'Toole make an endearing pair, and O'Toole eventually returned to the Superman universe by playing Martha Kent in TV's Smallville. Meanwhile, Margot Kidder openly criticised the Salkinds for their treatment of Richard Donner, and her reduced role here as Lois Lane seems like retaliation, as she only appears in two scenes. Although the Salkinds deny bad blood and claim that the Lois and Clark love story was overdone after the first two films, it is clear that the producers deliberately did her dirty here. Furthermore, Robert Vaughn is clearly a substitute for Gene Hackman's Lex Luthor, as their respective characters are somewhat similar. Hackman refused to return to the Superman II set after Donner's firing, making it unsurprising that he does not appear in Superman III, though the Salkinds insist that his absence was only due to Hackman's commitment to other projects.

Superman III contains kernels of good ideas, as it explores advancements in technology and the battle between good and evil, while the Lana Lang love story holds promise. Additionally, the film comes to life at times, particularly during the junkyard fight and a sequence where Superman rescues workers and extinguishes a fire at a chemical plant. However, Lester squanders the picture's potential by focusing too much on ineffective comedy. Simply put, Superman III does not feel like a true Superman movie, as the producers were more interested in capitalising on Richard Pryor's fame by creating a comedy rather than exploring more of Superman's mythos. Unfortunately, placing Pryor in the film did not boost its box office, as this threequel grossed less than half of its predecessor's worldwide haul, earning $80 million against its $39 million budget. Although the Salkinds wanted to pursue another picture, they eventually sold the rights to The Cannon Group, who produced a fourth instalment that is even worse. Even die-hard Superman fans should just watch Superman and Superman II: The Richard Donner Cut, and consider the series over.

4.2/10

Login

Login

Home

Home 183 Lists

183 Lists 1674 Reviews

1674 Reviews Collections

Collections

0 comments,

0 comments,